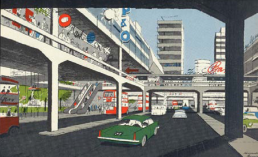

Since Buchanan’s “Traffic in Towns” report was first published in the 1960s the “predict and provide” approach has characterised the philosophy of transport planning in the UK; one of predicting future demand for travel and providing the necessary infrastructure to meet that demand, has unwittingly led to a primary focus on the motor car.

Some 30 years later, Prescott’s “New Deal for Transport” White Paper (1998) abandoned ‘predict and provide’ as unsustainable; however, despite a more sustainable approach to transport being promoted following the introduction of that Policy, the “predict and provide” approach for traffic has re-emerged a the key driver of transport demand.

This approach is still fully enshrined into our core planning policy, the National Planning Policy Framework; whilst it admirably sets out with a principle of “Promoting Sustainable Transport” the key policy test for the acceptability of transport impact, is still wholly focused on the car:

- Development should only be prevented or refused on highways grounds if there would be an unacceptable impact on highway safety, or the residual cumulative impacts on the road network would be severe.

The conundrum being, that maintaining such an approach will ultimately lead to the continual expansion of potentially unsustainable highway infrastructure to meet the latent demand for car usage. As transport and town planning professionals, we are all striving for a cleaner, more sustainable approach to transport and our environment, but ultimately the car has retained the king’s crown!

In 2016 Peter Jones, Professor of Transport and Sustainable Development at UCL (University College London) presented a paper entitled “Transport Planning: Turning The Process On Its Head”; Jones argues that a better approach to transport planning would be to focus on opportunities created by a “vision and validate” approach.

Vision: setting out and planning from the outset what we want ‘inspiring, sustainable growth’ to look like.

Validate: utilising exemplar design and modal shift forecasting techniques to test that vision, ensuring that our efforts will lead us to the best ways of eventually achieving it.

This approach would involve leading with a strong vision for how the future of our towns and cities should look and then assessing the types of investment that can be justified to support such a vision. To make this approach work, town planning professionals will need to develop a shared vision for any given town or city, and recognise that that the vision can be delivered by addressing broader societal and environmental issues.

It’s clear that the UK has been driving a lot less a during lockdown, the government published data saying that road trips in motorised vehicles, recorded at 275 automated sites, were at around 35% during April 2020 of the usual level, whilst levels of cycling have nearly tripled. These dramatic falls in road traffic have also resulted impacts that we have all noticed; less noise, congestion eradicated, safer streets and a improvement in air quality.

During the UK lockdown traffic simply disappeared!

However, this change has been forced upon us, and sadly has not been down to personal choice, but more out of necessity; architects, planners and urban designers have turned to predicting the endless possibilities of the future transport and suitable mobility; we’ve all witnessed the “vision”; the question is are we now really going to start validating it?

Whilst we may be on the cusp of the wave to achieving the aspirations that town planning professionals have been striving to achieve since the mid 90s; that unless we change our attitudes, and more importantly the policy makers do so, this welcome sentiment will inevitably evaporate as the lockdown eases.

Could “predict and provide” be a welcome casualty of COVID-19 and finally be replaced with a more holistic “vision & validate” approach, focused on the kind of towns and cities we want to live in, not ones that deal with residual traffic impacts!

If we are to continue the momentum we have gained in the last 12 weeks, beyond the knee jerk reaction of “pop up” initiatives, it will be down to our politicians, policy-makers, architects, planners, and engineers to raise this change to ensure that the “place-making” utopia we have all been seeking is delivered when we start to emerge from the pandemic; because if we don’t we will be left, as Buchanan said in the 60s, continuing to accommodate “The ‘Monster’ we love so dearly”